Adire – a Yoruba word which translates tie and die is indigenous to south-western Nigeria. It is made using a variety of resist – dyeing techniques. Rich in beauty, culture and history, Adire has become a fashion staple in present times which was not the case few years back, as this fashion piece was at risk of going extinct.

In this post we will be explaining the history of Adire textiles and its’ evolution through time.

Origin of Adire Textile

Adire textiles were first made by the Yoruba women using a variety of resis techniques. Guardian reports that adire was first produced in Nigeria in Jojola’s compound of Kemta (a center for cotton production) Abeokuta by the second Iyalode (Head of women) of Egba land – Chief Mrs. Miniya Jojla Soetan.

Using materials such as Teru (local white attire) and Elu (local dye) made from elu leaf (planted in the Saki area of Oyo State), the techniques were passed on for generations to come.

Although many regards Abeokuta as the Capital of Adire making in Nigeria, some suggest Ibadan and Osogbo – both Nigerian cities more important. This is because Adire dyeing began from when Egba women from Ibadan returned to Abeokuta with the knowledge.

The earliest pieces of Adire textiles were probably elementary tied designs on locally handspun and woven cotton cloth (These designs are still produced in Mali) called Kijipa. Heritage of handwoven cloth with indigo for use as wrappers and covering clothes can be retraced back to centuries in West Africa. A cap from the Dogon Kingdom in Mali dating to the 11th century dyed in the Oniko style is the earliest known proof.

Rise of Adire Textile

At the beginning of the 20th century, a vast trade network for adire spread across the West African region – sold as far as Congo, Senegal and neighboring countries including Ghana. End Result? A market boom that paved way for women dryers to become both artist and entrepreneurs due to access of imported shirting material in large quantities by Europeans.

Technological innovations to decorate adire made it possible for men to enter the female controlled industry – women still retained their dyeing forte and continued the process of tying, hand-painting and hand-sewing. Men however, took roles that involved machines – sewing machine stitching and application of star ch through zinc stencils, due to the perceived gender roles of West Africans.

Fall of Adire Textiles

Late 1930’s saw a decline of the craft as a result of the use of synthetic dyes, caustic soda and less skilled artisans. The restriction against the exportation of cloth to West Africa during World War II (1939 – 1945) by the European Government also had negative effects on the craft.

By 1945, Nigerian market was flooded with low-priced prints from Asian, European and African textile mills. Going forward to the 60’s adire textiles was regarded as “poor peoples cloth” not until the textile caught the attention of fashion designers who made an effort in rebranding the cloth, using imported color fast dyes other than indigo.

Mrs. Betty Okuboyejo who came to work and live in Nigeria is credited with introducing high-quality adire inspired designs using a full range of commercial colorfast dyes. Multicolored adire instantly became a hit in local markets.

In present times, simplified designs and better quality oniko and alabee designs are still produced but locals favor “Kampala” (a multi-colored wax resist cloths, popular at the time of the Kampala Peace Conference to settle the Biafra War in Nigeria.

New Adire Age

Nigerian artisan Nike Davies – Okundaye also known as Nike Okundaye, Seven Seven and Nike Olaniyi founder and director of four arts centers that offer free training to over 150 young artists has inspired a younger generation which include designers Amaka Osakwe (Maki Oh) and Duro Olowu – a revival of the Adire Movement.

Techniques Involved in Making Adire

Adire cloth begins with dyeing a white piece of material. Before it is dyed, it is treated in variety of ways to create a pattern that are revealed after dyeing. Today, there are three primary resist techniques used in Nigeria.

i. Eleko: Translated starch resist. Resist dyeing with starch made from cassava flour – Cassava starch enabled a greater variety of patterns. Cassava starch made from grinding and mixing cassava roots with water to form paste is applied traditionally with different size chicken feathers, calabash carved into different designs. Modern methods involve use of mental stencils – a comb like device.

Common stencil designs features King George V and Queen Mary – with images originally taken from souvenirs produced on 1935 to celebrate the silver jubilee.

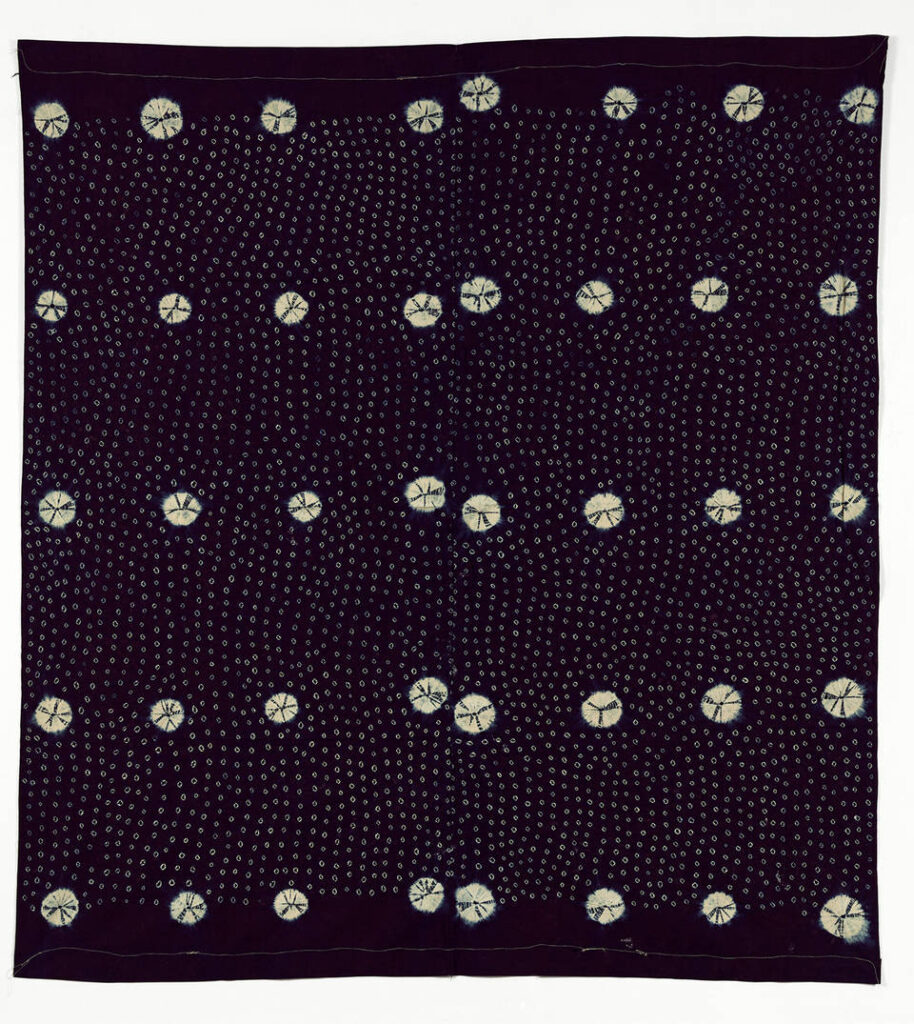

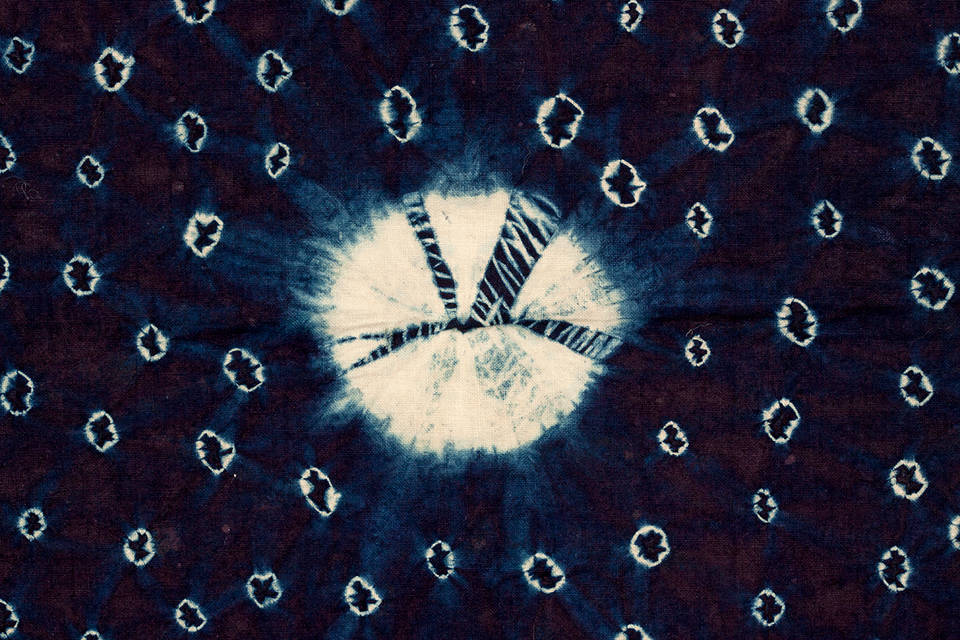

ii. Oniko: Translated raffia resist. Involves tying raffia around hundreds of individuals corn corn kernels or pebbles to produce small white circles on a blue background. Larger circles are made by lifting a point of fabric and then binding the fabric beneath it tightly.

The fabric can also be twisted and tied on itself or folded into stripes. Clothes made with this method were highly popular in the 60’s because it could be produced fast and cheap in response to customers varying designs. It was considered cloth of the year in 1964.

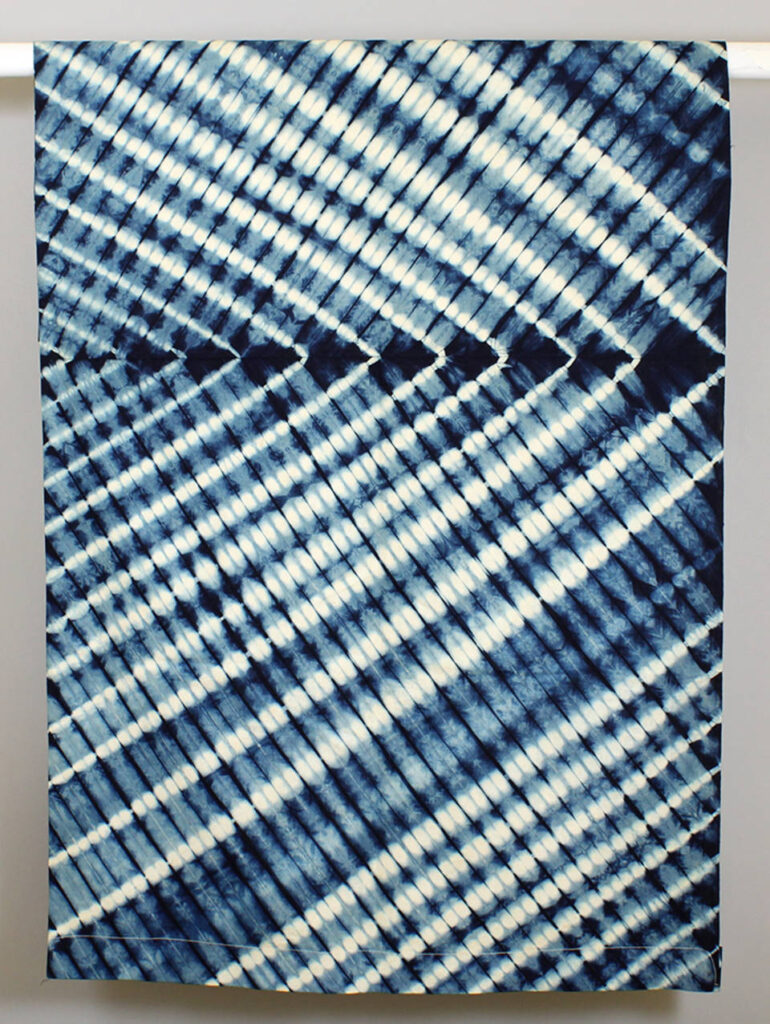

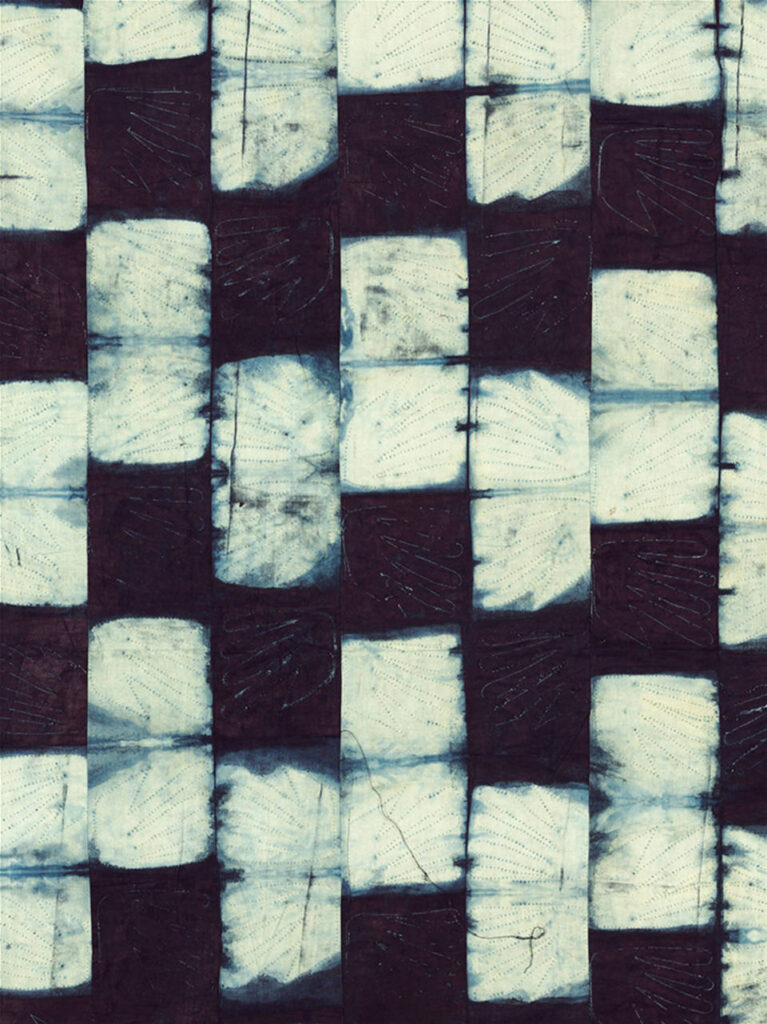

iii. Alabere: Translated Stitch resist involves stitching raffia onto the fabric in a pattern prior to sewing. Both machine and hand sewing can be used to produce patterns. The raffia palm is stripped first and the sewn into the fabric. After dying, the sewn spine is removed to reveal pattern.

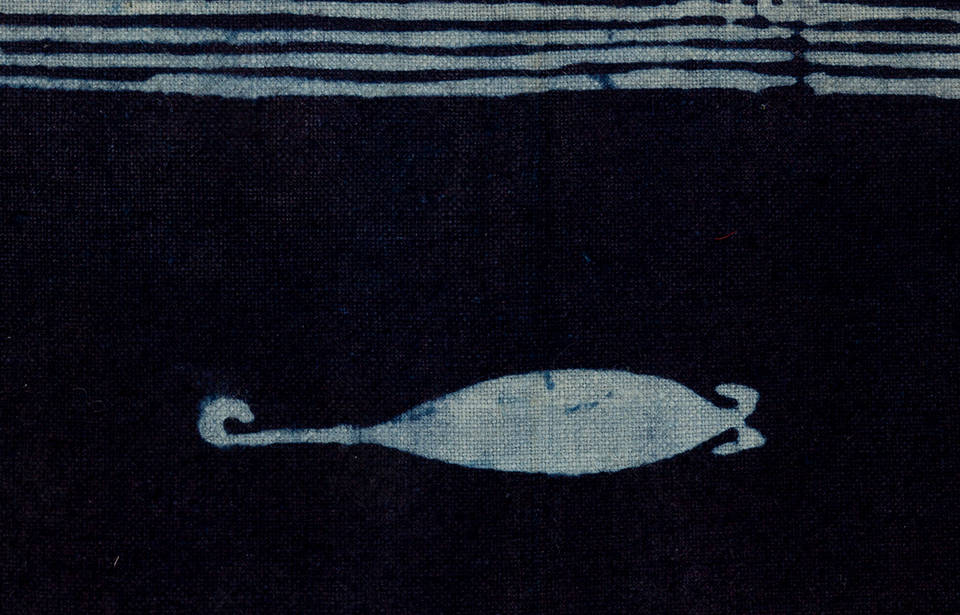

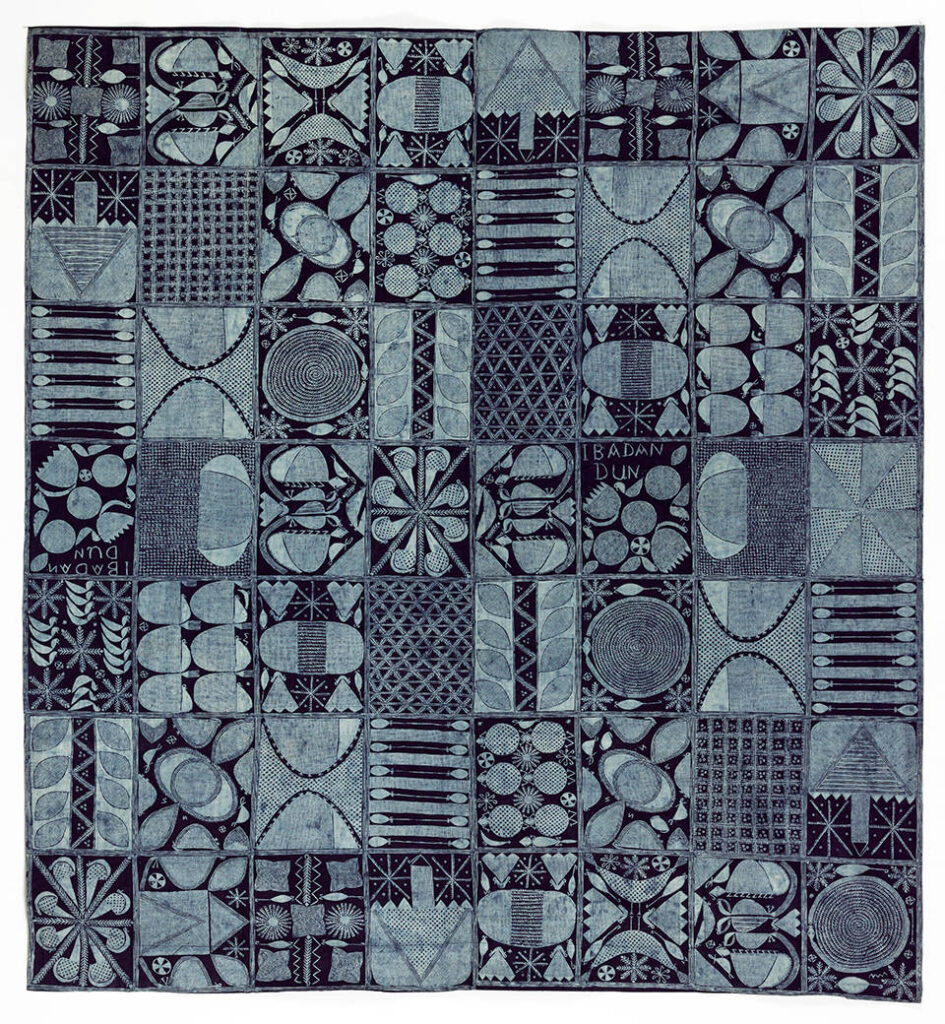

Ibadan Dun: Involves hand painting using chicken feathers, palm leaves and match sticks to create a range of patterns uniquely done by women of Ibadan. This labor intensive work is usually signed with a symbol by the artist who created the piece. The pillars of the city’s own hall and spoons were classic features in the Ibadan’s version of Adire.

Other designs named with popular names include Olokun (goddess of the sea) Sub=nbebe (lifting of the beeds)

Difference Between Tie and Dye in Nigeria with other African Countries

Nigeria’s resist designs are two-toned indigo resist designs which is created by repeat dyeing of the material which has already been painted with cassava root paste to create a deep blue color – the next step involves washing the paste out then dying the cloth one last time. For more quality the cloth is dyed 25 times or more to create a deep blue color before the paste is washed out.

In Mali, Bamana of Mali, unlike Nigeria uses mud resist, the Ndop of Cameroon use both stitch and wax resist while Senegalese dyers use rice paste instead of cassava root.

Vogue editor, Anna Wintour in #Tie&Dye

Studio 189 Spring 2020 Ready to Wear Fashion